My Favourite Football Book - The Glory Game

By Mark Meadowcroft | 23 March 2020As we all go on lock down, we’re going to need something decent to read – and while we may be limbering up for some classic fiction or an improving work about the future of society, if you’re seeing this, you are also in the market for something good on football.

There’s some fantastic stuff around that is widely known, but the greatest book on the greatest game is one that no City fan would take a second look at from its cover and subject matter and is barely known outside the fan base of the rival club that it effortlessly transcends.

I’m going to ask you to immerse yourself in the Tottenham Hotspur team of almost 50 years ago and to read a book by an author who is still alive and popped up at the age of 84 last week claiming that he’s not scared of Covid-19. OK boomer.

I am not really selling this very well, am I? But the identity of the club involved is exactly the least interesting about it by an author who, in his 1970s peak, was exceptional. Had it been written about City at the same time, the stories would have been different, but exactly the same.

The Glory Game by Hunter Davies, a fly-on-the-wall account of Spurs in 1971-72 is quite simply the best football book I have ever read. The premise is simple. Davies persuaded the club to let him go everywhere and speak to everyone. The changing room. The team coach. The training ground. Players’ homes. The club doctor and his annual talk about STDs. The manager’s wife. It makes look All or Nothing seem like a stage-managed, scripted exercise.

He made notes, wrote up the unvarnished truth and published it. Up to and including graphic medical discussions about the issues Alan and Kathy Mullery had had conceiving children. While Amazon Prime TV and Sir Ben Kingsley produced a revealing account of the Centurions season, it is nothing like what Davies saw and wrote.

There’s even a chapter where he makes the players answer some very open questions on class, politics and gender. Amazingly, most of them answer on the record and with deep honesty. In the world we live in now, these working class baby boomer Tories explain in their own words so much of the world we live in.

This was before media liaison, PR, brand management and image rights had even been thought of. Davies drives from London to Bristol and back again with the great Spurs manager Bill Nicholson, the central character in the book, who tells him on the M4 between Reading and Swindon exactly what he thinks of his players and explains in detail what would now be called his “philosophy.” It’s modern and hipsterish too. He’s also invited to a 1970s house-party at centre back Mike England’s Hertfordshire commuter belt house where he meets his neighbours and friends from the local Round Table.

No writer will ever get the same freedom again. Thankfully, Davies did not waste his opportunity.

Davies struck lucky with the season. Spurs played 65 hectic matches, reaching the semi-finals of the League Cup, the last eight of the FA Cup and finished on a huge high, winning the UEFA Cup, beating Wolves over two legs in a tie that has been all but written out of English football history. The marquee player, Martin Chivers, is still very much alive but outside Spurs seems an almost forgotten character these days. In 1972 he was a major star, a complete centre forward with the style and status of Alan Shearer or Harry Kane.

But he wisely starts the story on the first day of pre-season, evocatively comparing footballers getting their fitness back on hot July days with the grace and poise of Evonne Goolagong on Centre Court at Wimbledon the previous week and while swathes of matches are skipped, the book ends with contract and transfer negotiations the following May.

However, this is not a story of success, even though Chivers scored 44 goals that season, Bill Nicholson was a great manager, and amid a number of top class players, Chivers, Pat Jennings and Martin Peters were elite.

It’s the feeling of failure that pervades almost every page and which Davies describes so vividly and dispassionately. Because however good the team was, they could, should and had been even better. The tone was set by early season draws against teams they should have been beating, and pleasingly for this demographic, a late summer hammering at Maine Road courtesy of an excellent City side.

There’s also a brilliant description of a bad defeat at Coventry where Davies travels to the game on a football special, watches the match with a firm of hooligans and travels back to London on the team coach. The descriptions of coach trips and the UEFA cup ties in Romania, France and Italy are outstanding on the boredom, time-killing and infantilization of footballers’ lives. Because there’s nothing else to do, the conversation immediately veers towards money and women and stays there.

Spurs finished sixth, down from third the previous season. This was the year City looked likely winners until Rodney Marsh was signed and coincidentally or otherwise they lost back to back matches over Easter, letting in Brian Clough’s Derby County. But in spite of Chivers’ goal haul, Spurs were never in the argument – and the table immediately tells the story. Only three away wins and 10 draws tells you what you need to know.

Ageing Team

But that wasn’t the only reason. Very quickly it becomes clear that this is a team that isn’t getting any younger. Bill Nicholson is only in his early 50s, but his double-winning team was more than a decade in the past, and Davies casts Nicholson – seemingly outrageously but as it becomes clear, very astutely – as a man struggling to keep pace with the modern game. Tactics weren’t a problem, as Nicholson and his otherwise antediluvian assistant Eddie Baily were voracious students of the game and a mid-season formation tweak and clever set pieces were central to the team’s success, but he struggled to bond with or relate to his players. Partly this is generational. But he’s also a man with huge domain knowledge, an outstanding CV, a reputation for total fairness – the players were always given a face to face explanation of why they had been dropped and always accepted the reasonableness of the decision – but someone who found it increasingly difficult to praise.

Almost all of the players, and Chivers and Peters maybe more than any others, craved affirmation that was rarely forthcoming.

Decades later, we would have used phrases like “stale”, “end of cycle” and “needing a new challenge”. But Nicholson’s fierce pride forced him on. The tougher the challenge, the better he was able to motivate his team, most memorably when he inspires Chivers to score twice in the UEFA Cup final. The fire still burned bright, but not consistently. At other times, he’s obsessed with the hair length and trouser width of young men with money in their pockets in London in 1971.

The fact that the players reserved their best performances for Cup competitions, including a narrow two-legged win over AC Milan in the UEFA Cup semi-final, where this ageing but still talented team hauled themselves over the line with a mixture of quality and maximum effort, concentration and street smarts over 180 tense minutes was a source of equal pride and sorrow for Nicholson, whose frustration boiled over at some of the league performances at places like Coventry and Ipswich.

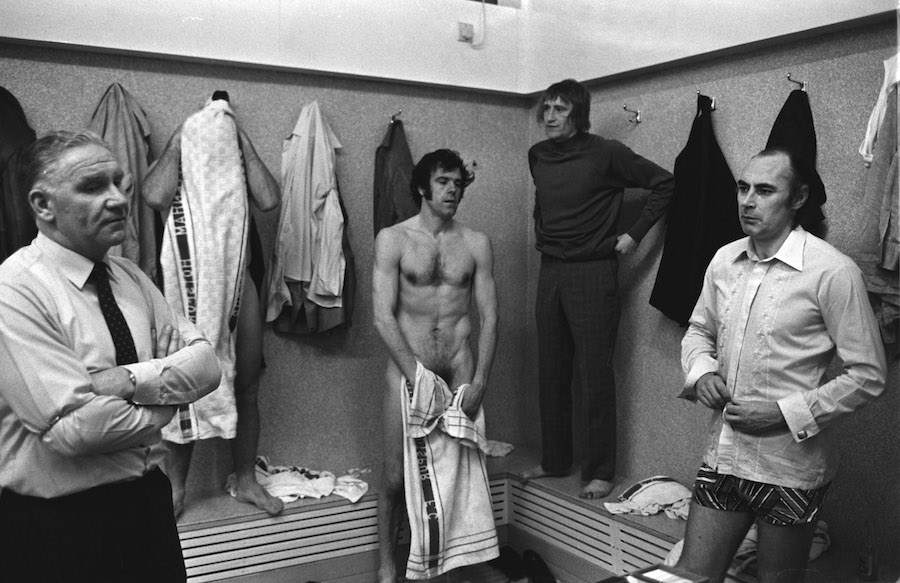

11/03/1972 Tottenham Hotspur v Derby County. Tottenham dressing room left to right: Bill Nicholson, Mike England, Terry Naylor and Alan Gilzean.

He also had to deal with his star player, Chivers. The relationship between the two is highly equivocal – guarded mutual respect and an understanding that 44 goals in a season brooks no serious argument combined with a shared inability to find a more constructive way of working together.

While Nicholson was a Yorkshireman and Chivers from the South Coast, both came from very similar backgrounds – sons of poor families bright enough to pass the 11 plus but too obsessed with sport and football to continue with education beyond 16, even though both could easily have done so.

The result is that both men are bright enough to wound each other emotionally but hadn’t been taught how to manage tense situations. There was no-one to mediate like there would be now. Nicholson was authoritarian and old school, but not without flexibility – he was Bill to his players – while Chivers, for all his out of control ego could speak very fondly of a manager he wanted to impress badly but never felt loved in the way Nicholson loved his 1961 players.

Chivers’ navigation of the early days of footballer celebrity, commercial endorsements and media engagement is very low rent to our eyes but fascinating. There was no previous generation to follow in these matters so he and his peers were making the rules. While Chivers embraced this life, Peters was totally disinterested and Alan Mullery was equivocal – a family man at heart, but one who admitted he enjoyed being appearing on TV to offer his opinions on football, hoped to be asked again and saw this as something he could do after retiring. Exactly like modern players.

Chivers and Nicholson didn’t dislike each other as such – in some ways it would have been easier if they had – but it was highly dysfunctional. Having this laid out page after page, match after match in almost forensic detail makes The Glory Game a book like no other.

Nicholson also harboured an unspoken but widely shared suspicion that his centre forward was a flat track bully who didn’t score heavy goals, at least until the UEFA Cup Final, when he scored twice to at last answer his sternest critic – and the only one the player had an emotional need to satisfy.

Chivers for his part seemed to have a nagging concern that he was playing for a team of cup specialists and that he could be at a club that was going forward rather than, at best, standing still. His legacy is maybe defined by the fact that he was never involved in a serious title challenge or an international tournament for England. The description of Chivers, the hints dropped of a crumbling marriage, the arrogance, the selfishness, are also timeless. But it’s probably impossible to score that weight of goals without ego and greed. And the other stuff is what happens when a 26 year old man has access to money, fame and the adulation of women, all of which he clearly liked. Of course the club offered him no help at all in navigating this.

The comparison is far from exact, but the echoes of Guardiola and Aguero in 2017 should be staggeringly obvious to any Blue. The fact that the two City men, maybe guided by their club, managed this so much better, is to everyone’s credit.

As for other key players, centre back Mike England is well into his 30s and is trusted by Nicholson. But the errors and poor games seem to happen with increasing frequency. When another defender, Cyril Knowles, makes an error that leads to Spurs losing to Chelsea in the League Cup semi final he is dropped. England was culpable in other matches but maybe because Nicholson was unconvinced by the alternatives, the axe never fell. At the end of the season, this situation is left deliciously unresolved.

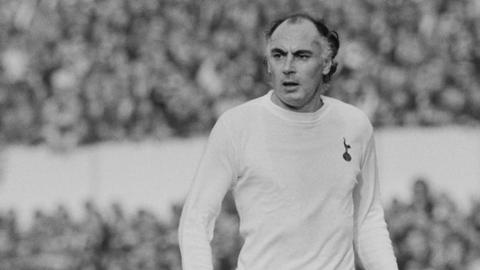

Mullery

Alan Mullery was always a player that divided opinion – Malcolm Allison famously did not rate him. But he had played with distinction at the 1970 World Cup, in spite of what Big Mal thought. The book captures Mullery as he turns 30 and struggles with persistent injury and loss of form. The Captain is out of the team, finding football a suddenly difficult game. But Mullery is the redemption story. In March, he’s sent on loan to Fulham, officially to get match fit but unofficially because Nicholson thinks he’s done. The red flag was Mullery getting bypassed by City early in the season. Nicholson didn’t react immediately because that match was also a Colin Bell masterclass. However, a UEFA Cup tie in France against Nantes was more worrying. The same thing happened against lower quality players.

However, injuries mean Nicholson is forced to recall him and he plays a major role as a goalscorer and leader in the UEFA Cup semi final and final. The decline in form was indeed partly caused by a pelvic injury that needed time to heal and the matches at Fulham did give him back his sharpness. But both sides accepted it was his last hurrah and that summer he leaves.

Davies’ description of Mullery is very sympathetic, an outstanding piece of writing about a man with a high opinion of himself but, behind the bluster, a very vulnerable, sensitive person trying to do the right thing for his wife and daughter, who are far closer to the centre of his life than football.

And then there’s Alan Gilzean, an even older player, a forward of rare skill, still a goalscorer and clever, intuitive strike partner for Chivers – but a heavy drinker on even more obviously borrowed time than Mullery or England. Davies writes almost elegiacally about Gilzean, who seems to be his favourite player, the sort of player Scotland used to produce constantly but even in the 1970s was beginning to dry up.

Trouble Ahead

So who is replacing these thirtysomethings? Nicholson has two problems. He had spent heavily and wisely in previous seasons on Peters and Chivers, but while Spurs could afford to pay large transfer fees, there were no players that could be auctioned for big money without seriously weakening the team. He couldn’t afford mistakes. The book dwells heavily on a signing that was both not working out and had the longest hair at the club.

He had bought Roger Morgan, who played with Rodney Marsh at QPR. He’d been OK on the rare occasions he was fit, but no more. In a nod to Paul Lake, Morgan is unconvinced that his injury has been managed well by the ancient medical staff at the club. He’s quite possibly right and by 1973 he had been forced to retire.

His kindly but flippant character grated with Nicholson – particularly as the academically able Morgan knew where the line was between wisecracks and sarcasm and a breach of the rules that the manager could punish. Nicholson went back into the market in the summer of 1971 and bought another player who played in Morgan’s position.

Ralph Coates becomes a major character. He’s not a bad player and not a bad signing – he ended up staying at Spurs for several seasons and becoming a bit of a cult hero – but he’s never more than acceptable and while he’s in the team that wins the UEFA Cup, he’s below the standard of Peters and Chivers. Davies’ description of Coates desperately trying to be the player Nicholson wants him to be but never will be is very moving. Nicholson’s reciprocal acceptance of the fact is also beautifully written. It’s not for a lack of effort but Nicholson’s error is clear. He thought he was buying a top class winger. He actually got a decent, hard-working but overpriced midfielder who offered good but not elite service.

Then there are the squad players. But there’s a problem. They’re not really challenging the established players. Barry Daines, Terry Naylor, Tony Want, John Pratt, Jimmy Pearce. All contribute at times but only Ray Evans is of a similar standard to the player they are employed to compete with. They’re drawn in vignette by Davies, but none are ultimately quite good enough – although some of them are promoted in later years as first team players leave and are not replaced and the team declines . The 1971-72 starting eleven know they are safe and that may be one reason they consistently play far better at White Hart Lane than away from home. One youth team player gets an intriguing walk-on part. A teenage Graeme Souness was on the fringe of the squad, about to step up. But he never does, and drifts out of the club and on to Middlesbrough.

Davies is also fascinated by the hangers-on, family members and non-playing staff on the edge of the narrative. Several versions of fandom are described from the wealthy friends of the players to the Official Supporters Club and of course the Firms. Many of the players (and Nicholson) are very uxorious but collectively the women are treated objectionably. Racism is casual and accepted, although the late Cyril Knowles deserves credit for calling it out when it wasn’t a risk-free option.

But the atmosphere is set from the top. If the players are ageing, the magnificently-named Club Chairman Sidney Wale is an extremely elderly 58 year old, written by Davies as being principally concerned with the twin evils of perimeter board advertising and women in the boardroom on match days.

To be fair to Wale, he does get some big things right. The club is financially, institutionally and managerially stable, Nicholson makes all the playing decisions and while he makes polite conversation with the players, he keeps his distance and is respected for that.

Ludicrous commercialisation of football grinds all our gears. But the extreme conservatism of Wale sets the atmosphere Nicholson and his players have to work in. The best players at the club are well off with nice stockbroker belt detached houses. They may drive a Jaguar. If not, it’s a well-specced Rover or Ford Zodiac, but the club does not allow the players to realise anything like their earning potential. Spurs in 1972 are an old club, getting older off the pitch as well as on it.

The End

And we know how the story ends. The following season, Spurs win the League Cup and reach the semi finals of the UEFA cup, this time losing to Shankly’s Liverpool. Sixth in the league turns into 8th. In 1974, with Mike England still playing, they somehow reach the UEFA Cup final again before losing comfortably to Feyenoord. But that is the end, the following season Nicholson leaves and they are almost relegated and in 1977 they do go down.

The Glory Game is a chronicle of a decline foretold.

It’s just a delicious piece of writing, the first, greatest and longest read of the now commonplace cracked badge genre. I don’t think there will ever be a more accurate account of what it is really like to be on the inside of an elite football squad, because no-one would ever let someone have the access Davies got, and even then the writing it provokes is hugely unlikely to be even close to the same standard.

After a while, the name of the team ceases to matter to the reader. We are talking about real life, about people, about motivation and the passing of time. As a City fan, not only is it an unputdownable read because it’s football and it is quite beautifully written, it is also a barometer and a warning. This is what to look for when football clubs with great managers and fine players imperceptibly begin to go into decline.

The book ends with a European Trophy. It’s a successful season – borderline great – but Davies has just spent hundreds of pages pitilessly describing a downward trajectory. The stench of decay is mild but everywhere, a team and a manager in their autumn. This book is a masterpiece and will keep you company through isolation and lockdown. It’s set at Tottenham Hotspur but beyond the names and the events, it is universal. I would recommend it unhesitatingly to any City fan.